HOW TO ... detect early warning signs of recovery in complex systems

Short summary of a recent paper by Clements, McCarthy and Blanchard

Image credit: curiosityandheroin.org

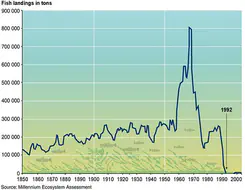

Image credit: curiosityandheroin.orgBeing able to foresee if or when something bad is going to happen has always been considered very useful as it allows for the adoption of new strategies in the hope of avoiding catastrophe or for the adaptation to the new circumstances. Applied to the context of fisheries and marine ecosystem, this means being able to predict the outcomes of actual and potential fishing regimes and environmental conditions on a particular fish stock, or an entire ecosystem, a feat that is already possible. In contrast, forecasting of positive transitions, such as recovery from collapse, has not received anywhere near the amount of attention despite its potentially critical role in assessing the effectiveness of conservation or management strategies. In a recent paper published in Nature Communications, Clements, McCarthy and Blanchard (2019) have investigated abundance and trait-based warning signals that are detectable prior to stock recovery in order to assess the likelihood of recovery of the cod and other groundfish stocks in the Northwest Atlantic which iconically collapsed in the early 1990s.

So how does one go about predicting recovery? Before we dive into that, I would like to introduce the most important underlying ecological concepts, namely alternative stable states and hysteresis. Hysteresis describes the ability of ecosystems to exist in multiple stable states, or equilibria, under the same or similar environmental conditions. Which alternative stable state a system occupies depends on the history of the system and the disturbances it has been exposed to (such as fishing, pollution, habitat destruction etc.). The transition between the two equilibria is called tipping point, and is often abrupt and difficult, but not impossible (this is very important, and I will come back to it in a moment), to reverse. To avoid these abrupt transitions between alternative stable states, associated with population collapse and hysteresis, abundance and trait-based early warning signals have been developed to predict the collapse of ecological systems.

What are abundance and trait-based early warning signals of collapse (EWSCs)? Abundance-based signals have been derived from the theory of critical slowing down (CSD), whereby a system shows a declining ability to return to equilibrium after a disturbance (such as high fishing pressure), driven by a decline in its resilience near phase/state transitions. Statistically, this can, for example, be inferred from increasing autocorrelation and variance in population count data collected over a period of time. Trait-based signals are defined as shifts in the mean and distribution of a fitness-related phenotypic trait, such as body size. These abundance and trait-based tools have the potential to predict population or ecosystem collapse by predicting the tipping point between two stable states. One fact that is often overlooked, however, is that a tipping point can be approached from both directions, towards recovery as well as towards collapse: If the equilibrium at hand is a population, community or ecosystem in the collapsed state, warning signals, potentially opposite to those of collapse, are still expected to be present.

Why should anybody care about predicting recovery? As suggested before, being able to predict the likelihood of recovery of collapsed populations, communities or ecosystems under certain conservation and management regimes would be very valuable for the assessment of efficacy of said regimes. It would, furthermore, allow the allocation of often limited resources to management strategies that are highly likely to have a beneficial effect on the intended target. In addition, the relatively small amount of data needed to predict a system’s future state, even for rather complex systems, is a major advantage of this approach. The authors suggest that this might make this approach especially useful to developing nations, where the means for in-depth understanding of complex exploited systems may be lacking.

As this is only a brief overview of the full article, make sure to read the whole thing on Nature Communications.